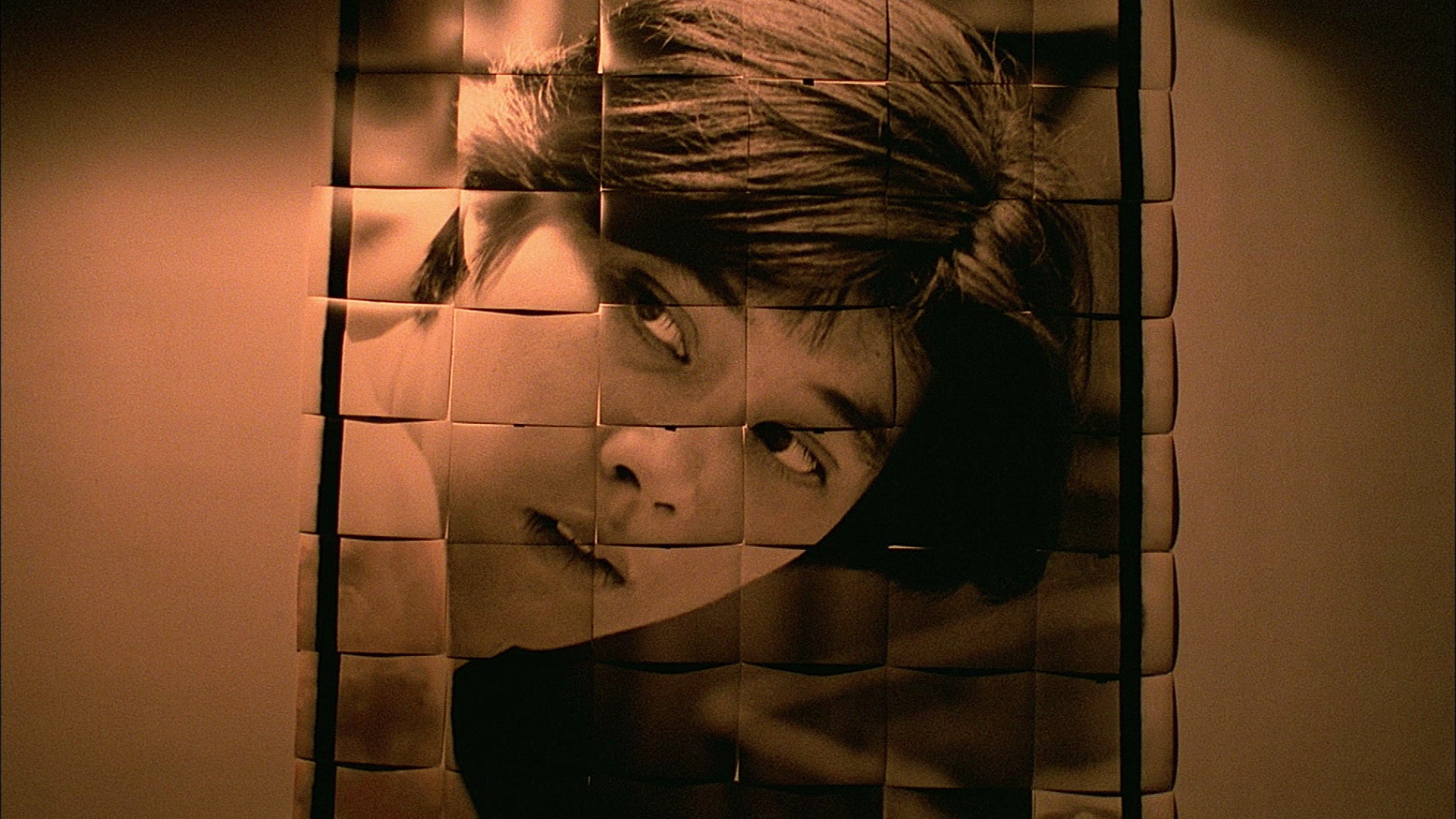

A transcultural film voyage into the recent past with 14 stops along the way.

Each weekend, Time Machine: 1986-2000, the film programme of the Santa Barbara season, will make a stop in the past between 1986 and 2000, that is, from the start of perestroika to the end of Boris Yeltsin’s presidency. The rules are simple: each year is represented by two films, one Russian language and the other a foreign language film. They may have been filmed at that time, or taken “off the shelf” then (that is, officially released that year), or they may describe that year retrospectively. The paired movies sometimes complement each other, but often present opposing views, giving equal space to alternative interpretations and demonstrating a variety of views and voices, from which it is impossible to cobble together a single story.

Time Machine: 1986-2000 is not confined to a particular genre, school or national cinema. On the contrary, it focuses on the authors’ voice, vision, statements and transcultural nature, switching between Hong Kong, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Belgium and Russia.

Despite the heavily retrospective nature of the programme, some films will be shown in Russia on the big screen for the first time. An example is the cult film The Killer by John Woo (1989), a forerunner of The Matrix. At

An important event is the return of major Russian films from the last decade of the 20th century to the big screen: Pavel Lungin’s Taxi Blues (1990); Valery Todorovsky’s Love (1991); Moslem by Vladimir Khotinenko (1995); and 8 ½ $ by Grigory Konstantinopolsky (1999). Each of these conveys a sense of time on fast forward and outlines important elements of auteur style (for example, the female characters in a Todorovsky film or the signature farce of Konstantinopolsky).

Two minor retrospectives are also part of Time Machine: 1986-2000. One of them is devoted to Andrei Konchalovsky’s timeless two-part classic (The Story of Asya Klyachina…, Asya and the Hen with the Golden Eggs), another to the surly joker and true native of the 1990s, Alexei Balabanov (Brother, Dead Man’s Bluff).

A year is something of a guideline with a dual purpose. On the one hand, through the classics we can try to abandon the idea of “catching up”, a cornerstone of our culture. The Russian countryside and its fabled backwardness, Soviet slogans like “catch up and overtake”, constant calls for accelerated modernization, imperial obsessions — these were all bars of a beautiful cage, a stimulus and an inspiration yet at the same time a mouse trap that snapped shut long ago. On the other hand, it is an opportunity to keep from slipping back into the rut of Russia’s "special path" that supposedly explains everything. Time Machine: 1986-2000 uses many examples to show that all paths in the world intersect; they are similar yet different.